Strange Weather: New Paintings by Joy Garnett

Lucy R. Lippard

In a period when media-influenced imagery and digital mediums are ubiquitous in the mainstream art world, Joy Garnett has perversely gone in the other direction. As a self-described “information junkie,” her sources are photographs from the news media in the five years since September 11th, 2001. But as an artist determined to control her own means of production, she makes good old-fashioned landscape paintings…with a twist.

Garnett sees her process in terms of Open Source Culture (OSC) — the more-or-less public reservoir from which anyone can drink deeply of imagery initially intended for a sip at best. She describes this apparently new system, available for translation, transformation, or appropriation, as “really the longstanding operative principle for innovation… Nothing comes out of thin air.” Thus her work parallels that of collagists and appropriators — software hackers, DJ samplers and a number of artists. But these straightforward paintings are not visual collages so much as conceptual collages; the comments on art and technology are invisible, while the planetary/atmospheric ramifications take front stage.

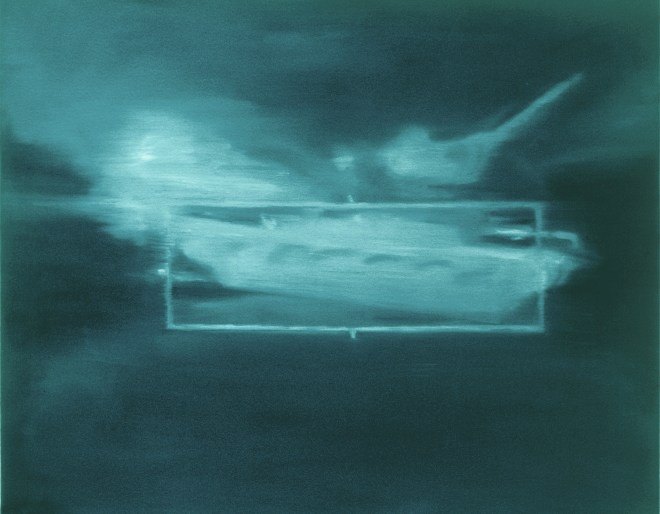

“Strange Weather” is an astute understatement for what the world is undergoing. Equally strange is the apathy with which news of cataclysmic change is being received. Garnett’s work reflects that change in a deceptively conventional manner. We have all seen a plethora of images — from the news and from art photographers — of the devastation wrought by hurricane Katrina. But when we see those images, usually perceived/received so fast they barely register, translated into independent works of art, they are less recognizable. Flood 3 becomes a majestic icon of destruction in the fall-of-empire genre.

First we are immersed in the great billows of paint — smoke and clouds, shards of fire, bodies of land — then we move on to the context. The apocalyptic nature of the events depicted is most evident in the skies. Some are operatically dramatic, others are eerily calming, color alone conveying the unusual. Art history is evoked only to be revoked. Evac is half sky, half land like many Dutch 17th-century canvases; Flood 5 and Plume 2 evoke the ominous sublime of monumental 19th-century landscapes. Devastation is understated in Live Oak, where the great old tree (many were victims of the storm) recalls early Mondrian. The rising waters appear peaceful and beneficent; they are in fact lethal.

Landscape painting contains its own paradoxes in these days of photographic ascendancy, when photographs have finally been recognized as no more “truthful” than any other medium. Curiously, the distance afforded by a painting permits a more intimate experience of the effects of Katrina than the fragmented, momentary blitz of media photography. By reinventing her photographic sources, Garnett gives us time to be there, in place, on solid ground, however terrifying that may be. Simultaneously, by merging political and physical phenomena, she pulls the rug out from under our previous sources of information, perhaps even making us nostalgic for the impersonal flashes of media imagery that allow us to avoid responsibility for the environmental and social catastrophes we face.

Copyright Lucy R. Lippard 2006

National Academy of Sciences (U.S.), J. D. Talasek, Alana Quinn, and Lee Boot. Convergence: The Art Collection of the National Academy of Sciences. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 2012.

Strange Weather, exhibition catalog, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, 2007.

Lucy R. Lippard is an internationally known writer, activist and curator. She has written eighteen books on contemporary art, and is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Frank Mather Award for Criticism from the College Art Association, and two National Endowment for the Arts grants in criticism.

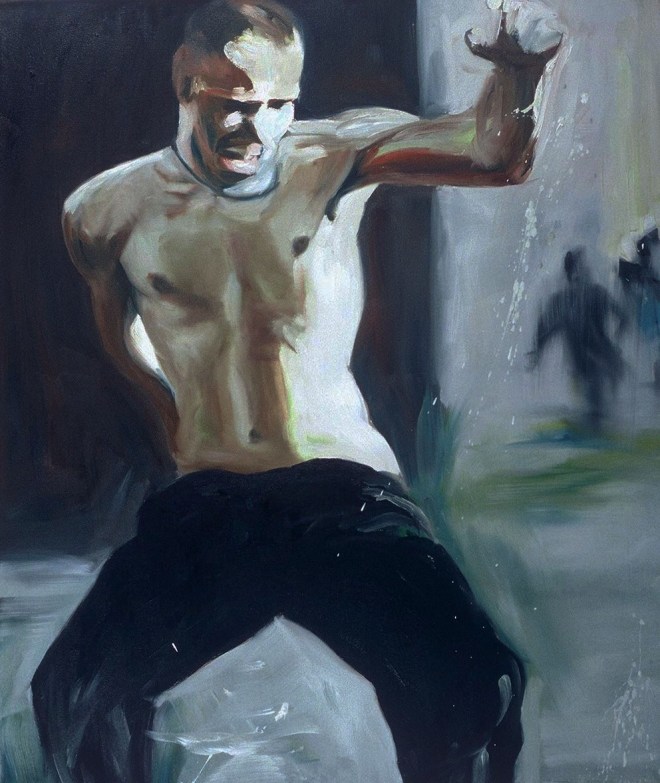

Paris Riots 2005

Joy Garnett

PARIS RIOTS: When we speak of citizen journalism, many of us think of the Arab Spring and Egypt’s youth movement launched on January 25, 2011 with its reliance on smartphones, social media and viral video. As one Egyptian activist tweeted, “We use Facebook to schedule the protests, Twitter to coordinate, and YouTube to tell the world.” Only a few years earlier, in 2005—before the advent of Facebook and Twitter—protests and riots raged on the outskirts of Paris, sparked by the accidental deaths of two young boys who were hiding from police in an electrical substation in Clichy-sous-Bois. The rioting spread throughout the Île-de-France and eventually to the suburbs of other cities, giving expression to the hopelessness of a generation of marginalized youth, the children of predominantly Arab, African and North African immigrants, stuck in ghetto high-rises in the banlieues. Over several months, more than 9,000 vehicles were set on fire, as well as scores of public businesses; France declared a state of national emergency. A government-imposed media blackout sent journalists scurrying for imagery, which they found posted on personal blogs, YouTube and Flickr: lo-res images and video of burning cars and riot police, shot by ordinary people on the ground with cheap cameras and rudimentary phones. These images served as immediate and authentic documents, and are a precursor to subsequent uses of social media as tools for dissent. I painted my Paris Riots series based on a handful of lo-res images that were circulating on Flickr and elsewhere as the riots unfolded. The paintings are small but fiery like their source images, and speak to the urgent need to communicate what was happening on the ground. But unlike the digital images, the paintings embody physical space, and they instill, through the materiality of the gesture and the paint, the urgent physicality of the moment. Hence, the paintings offer the possibility of a different kind of engagement from what we’re used to when confronting political conflagration: the proximity afforded by the physical object, as opposed to the virtual image, more than a decade after the riots.

NY Chelsea Art District On Fire 2004 – full series

Riot 2003 – full series

Rocket Science 1999-2001 – full series

Buster-Jangle 1997-1998 – full series

…

You must be logged in to post a comment.